Aug 17, 2010 10

The Really Real, Totally Authentic Thing

If you don’t have time to blog then don’t. Ghost blogging is inauthentic & the antithesis of everything social. #dontbeafake cc @mitchjoel – Avinash Kaushik

If you don’t have time to blog then don’t. Ghost blogging is inauthentic & the antithesis of everything social. #dontbeafake cc @mitchjoel – Avinash Kaushik

When I was in graduate school, there was a lot of talk about the “death of the author.” Such talk was driven primarily by French, post-structuralist thinkers like Barthes, Foucault, Derrida, Deleuze, and Lacan who had an intensely nuanced and complex notion of writing and authorship that tended to highlight the supra-personal in any putatively “personal” utterance or authorial gesture. Steeped in such thinking, I became very skeptical of attempts to say with certainty who the “who” is when we ask, “Who wrote this?”

Barthes et al. were responding to various French philosophical currents of the 20th century but especially, I believe, existentialism. Whereas existentialism had put the individual human being at the center of (an ultimately meaningless) existence, thus hoping to establish a new moral center following the death of God, the post-structuralists chose instead to show that the individual was not the center of anything but, rather, the effect of many things (language, culture, discourse, the unconscious, etc.).

The French were not the first or the only critics to suggest that the individual (sometimes called “the subject”) was epiphenomenal. Freud had certainly pointed in this direction when developing his psycho-analytic theories as had Nietzsche a decade or so before him, Marx a decade or so before that, and Hegel at the very outset of the 19th century. But even these gentlemen were not the first to insist on the essentially contingent nature of individual identity which, in one form or another, can be traced back to the teachings of Buddha and even the Vedic authors before him.

Which is all to say that when I read things like Mitch Joel’s recent blog post on “ghost blogging,” my philosophical buttons get pushed.

Conceding that there may be practical value to ghost blogging (“I get that people Ghost Blog and it works”), Mitch shows that his opposition to it is, more than anything else, a matter of faith. Like a Luther for the Twitterati, he writes, “I believe this one thought (and I will stand by it): corporate Blogs being presented as a personal space to share insights have a predisposed and inherent understanding that the person whose name is on it is the actual author.”

You see, Mitch is less concerned with the value of ghost blogging than he is with values or, as he puts it, “ideals” (“I do think that there are some commonly held ideals within Social Media”) which he also refers to as the “pillars of what makes something ‘social’.” These pillars being, “transparency, openness, honesty, human and real voices (not corporate mumbo jumbo) and a culture that embraces sharing between these real voices.”

In other words, Mitch is a moralist who even indulges in the classic rhetorical move of the moralist, the value-laden leading question: “Why is everyone who defends ghost blogging so afraid to state that ghost blogging’s first act is one of deceit and misdirection?”

The philosopher in me wishes merely to point out that expressions like “actual author,” “real voices,” “human,” “social” and so on are not unproblematic.

What, after all, is an author and how does an author, generally speaking, differ from an “actual” author? What makes a voice “real,” particularly when we are talking about written texts (blogs) where the notion of “voice” itself is metaphorical? What attributes belong to the category “human” and what happens when “humanness” is invoked as an ethical category? Since when is the “social” defined by “honesty, transparency, and openness” rather than by concepts like “convention” or “conflict”? Etc.

I’m not sure that Mitch Joel is interested in the history of philosophy, let alone the history of the “ideals” that he invokes. Indeed, I’m fairly certain that he would dismiss my argument—that, in essence, concepts like authorship, or authenticity for that matter, are over-determined, social constructs which in no way represent uncontested, universal values—as equivocation. I am, after all, a ghost blogger whose work goes undisclosed by my clients. Thus, in the eyes of Mitch Joel, Avinash Kaushik, and others, I’m an aider and abettor of unreconstructed frauds and deceivers.

In my “defense,” and in answer to Mitch’s inherently unanswerable question (shades of “How frequently do you beat your wife?”), I would say that, if I am afraid to state that my first act every morning is one of deceit and misdirection, it is because I fear saying something that I do not consider to be true. Rightly or wrongly, I actually believe that the people whose bloggings I facilitate are the “actual” authors of the posts that I produce. The ideas are theirs, the “voice” is theirs, the blog is theirs, etc.

That being said, on a “human” level I resent the jargon of authenticity which pervades social media. When someone says, in the imperative voice, “Don’t be a fake,” I bristle. Why? Because I find the division of human actions into “real” and “fake” itself dehumanizing. Where does the notion of “authenticity” come from anyway? It is a term of trade driven by the desire to differentiate the genuine from the counterfeit so that an item can be assigned a monetary value. “Authentically human” is just another way of saying “Genuine leather.”

When we demand that humans be “authentic,” or criticize them for being fake, it’s because we have reduced them to the status of commodities. In fact, I believe that the social media, rather than humanizing marketing, as Mitch Joel and others have long hoped, have in fact completed the total colonization of human thought and affect by market forces.

Given the absolute assimilation of our lives by the new media, down to the most trivial whims (“I just ate a donut covered in bacon!” “I hate Justin Bieber”), isn’t it possible that the only way to hang on to our humanity is through masks, personae, and “ghosts”?

Or, in the immortal words of Robert Plant, “When you fake it, baby, please, fake it right.”

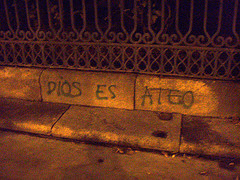

Image Source: Nick Wheeler.