Seems like nowadays, authentic is the thing to be.

Seems like nowadays, authentic is the thing to be.

Mitch Joel calls authenticity, “the cost of admission” in the Web 2.0 world, though he warns: “Being authentic isn’t always good. Let me correct that, being authentic is always good, but the output of being authentic [ie, revealing your flaws, shortcomings, and “warts” – Matt] is sometimes pretty ugly.”

HubSpot TV called the “marketing takeaway” of a notorious scandal involving a company paying for positive online reviews: “Be authentic. If not, you will get caught.”

When CC Chapman was among the Twitterati recently profiled by the Boston Globe, one of his Facebook friends asked, “Ever wondered why you have such a following?” He responded, “I wonder it all the time actually. I asked once and the general theme in the answers was my honest approach between life, family and work when it came to sharing things.” To which another friend replied, “Exactly right CC. You don’t try to be someone you’re not. It’s that authenticity that attracts people.”

Among the first to identify this flight to authenticity were James H. Gilmore & B. Joseph Pine II, who wrote Authenticity: What Consumers Really Want (2007). What notably separates them from contemporary partisans of authenticity is that their take is tinged with irony, an irony most evident in their promise to define “how companies can render their offerings as “really real.”’

This irony is refreshing because invocations of authenticity regularly fail to acknowledge or appreciate what is inherently contradictory about the concept. Said failure begins with the mistaken equation of authenticity and honesty (see above). Honesty may be a characteristic of an individual, but it is not a characteristic of authenticity. For example, an authentically honest person is being “authentic” when she is being honest, but an authentically devious person is being just as authentic when he is lying.

Similarly, we don’t call a painting an “authentic Rembrandt” because it is honest; we call it authentic because it was really painted by Rembrandt, unlike the forgery which only looks like it was painted by him. In other words, we call it authentic because it is what it seems to be. Herein lies the essential contradiction of authenticity: Authenticity isn’t about being real; authenticity is about really being what you seem to be.

The centrality of “seeming” to authenticity becomes even more clear when we call a person “authentic.” Such a designation usually means, “the way this person acts transparently or guilelessly reflects who they really are.” Because our sense of their authenticity depends on an assessment a person’s behavior, we should pay special attention to the fact that authenticity is performed; as paradoxical as it may sound, authenticity is an “act,” in the theatrical sense. (Which is why I always say, “Be yourself. It’s the perfect disguise.”)

The bigger problem though, is that our notion of authenticity assumes we really know who someone is and likewise the imperative to “be authentic” assumes we know who we really are.

Our identity, “who we really are,” is always contingent, provisional, and changing. It is an amalgam of who we want to be, who we mean to be, who we’re supposed to be, who we have to be, and who we are in spite of ourselves. Moreover, no matter how much we’d like to think so, we are not the authority on who we really are since it includes much that cannot be known by us. Indeed, and again paradoxically, we can’t know anything about ourselves without assuming the perspective of another, that is by identifying with someone else and precisely NOT being ourselves.

Just as one must consult an expert to determine the authenticity of a treasured heirloom – it can’t speak for itself – we can’t call ourselves “authentic;” that is for others to decide. At best, and this is the irony, we can always only strive to “seem” authentic. True authenticity calls for acknowledging that “who you are” is an open question and, moreover, a collaborative work in progress.

In the end, we must distance ourselves from our claims or pretensions to authenticity. We must call it into question and even suggest, especially to ourselves, that it may just be a ego-driven pose. (Hey, it just may be!) This distancing, implicitly critical and potentially mocking (or at least deprecating), is the classic stance of irony. And though the dodginess of irony (“did he mean that or didn’t he?”) seems to put it at a distinct remove from authenticity (“this is exactly what I think”), it actually mirrors the open-ended, unresolved, and ever-changing “dodginess” of reality itself.

Which is to say that irony, as a posture, an attitude, and as an approach, is more authentic (in the sense of “really being the way reality seems to be”) than honesty, sincerity, openness, or any of the other qualities that pass for such. The tragedy (or irony) is, however, that it will always seems less than authentic due to the all-too-human suspicion of ambiguity, indeterminacy, uncertainty, and, lest we forget, the wily intelligence native to irony and the ironist.

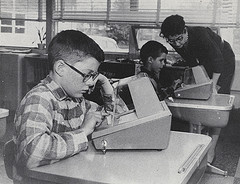

Image Courtesy of Mary Hockenbery.