Jan 9, 2012 1

Does Intensity Belong in Music?

I came to consider the question posed in the title of this post after seeing Tinariwen on a Friday night and then, three days later, Mastodon and Dillinger Escape Plan.

I came to consider the question posed in the title of this post after seeing Tinariwen on a Friday night and then, three days later, Mastodon and Dillinger Escape Plan.

The second concert was undeniably “intense.”

Dillinger Escape Plan play a frenetic brand of mathcore—the demonic love-child of hardcore and metal (particularly of the “technical death” variety). From the second they started playing, they were in constant motion, careening around the stage, jumping off everything. The singer taunted the audience by implying that they were not as extreme as the crowd in NYC, but eventually dove into the mayhem. Their performance frequently made me cackle in glee, on account of its ridiculous extremity. My friend Emmanuel said, “This band makes me feel like I’m 80 years old.”

Mastodon, the headliners, were thunderous and epic. Heavier than Dillinger, they were less dynamic, their klangwelt less varied, but they were also undeniably the crowd’s favorites. Propelled by a poly-limbed drummer and an impressive collection of riffs, their set bludgeoned and exhausted me, ending with the anthemic “Creature Lives,” the stage filled with people, every voice joined in a kind of viking chorus. I felt transported (at least for a moment).

Born of volume, velocity, and insistent, concussive rhythms, the intensity of this concert was something I had to physically endure.

The first concert of the weekend featured, as I mentioned already, Tinariwen. Made up of Taureg tribesmen adorned in colorful desert robes, Tinariwen plays a trance-y, guitar-driven, North African folk blues. They sing in Temashek, their lyrics a mixture of politics (the Tuaregs have long been at odds, and even all out war, with the central government of Mali) and Saharan melancholy.

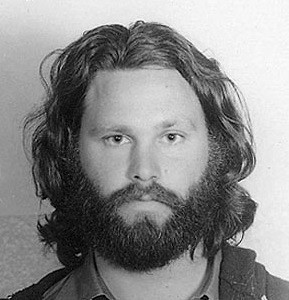

Occupying the opposite end of the intensity spectrum—about as far away from Dillinger as you could get—was Tinariwen’s leader, Ibrahim Ag Alhabib, who, according to Wikipedia, “at age four witnessed the execution of his father (a Tuareg rebel) during a 1963 uprising” and, as a young man, received military training at the behest of Muammar Ghaddafi.

Standing on stage, Alhabib was taciturn, inscrutable, slowly swinging his guitar back and forth, singing with his mouth barely moving. His was not an intensity that overpowers so much as one that draws everything into itself like a neutron star. The music was hypnotic, weaving a spell. I couldn’t help but move, turning around a distant fire in an endless night, orbiting a source of power that was deep and enduring like the ever-growing desert.

Look, I like the loud version of intensity, but the quiet intensity of Tinariwen meant so much more to me. It wasn’t the intensity of performance and display, it was the intensity of a lived life taking the time to quietly express itself in rhythm and melody. It was a human and even healing intensity.

The intensity of Mastodon and, especially, the Dillinger Escape Plan felt more like an imagined antidote to boredom in the face of our culture’s incessant barrage of superficial stimulus and cheap (even stolen) entertainment, as if they could create, as an aesthetic experience, the intensity that produced Tinariwen.

Unfortunately/fortunately, only real life can do that.