My posts on Aquent’s blog sometimes got kind of philosophical. Here’s an example which should help you dodge the question, “What do you want to do with your life?” It first appeared on September 20, 2008. – Matt

About twenty years ago, after I had stopped out of grad school, quit my job at SuperShuttle, and was so broke that I made all my family members collages as Christmas presents, my father sat me down for a fireside chat. The gist was: Dude, you got to get it together, figure out what you want to do with your life, and just do it. The problem was, as he put it, “You don’t seem to do anything.”

About twenty years ago, after I had stopped out of grad school, quit my job at SuperShuttle, and was so broke that I made all my family members collages as Christmas presents, my father sat me down for a fireside chat. The gist was: Dude, you got to get it together, figure out what you want to do with your life, and just do it. The problem was, as he put it, “You don’t seem to do anything.”

Was I a lost soul at that point? I suppose I was. My band (Spanking Machine) wasn’t going anywhere, I was unemployed, and, frankly, very depressed. When I returned to San Francisco from that demoralizing holiday in Los Angeles, I got a temp job (thus launching my current career, oddly enough) and wrote my father a letter.

Aside from the fact that the main point of the letter was to ask him for money so I could fix my car (yes, I did that), I also took issue with his criticism of my do-nothing lifestyle. On the one hand, as I pointed out, I did actually do stuff like write page after page of mad-cap, beatnik musings, play music, and hang out with my friends. I also reminded him that there were quite a few cultural and spiritual traditions that emphasized doing nothing over doing something as the true goal of life and enlightenment and that I was not unsympathetic to such views. Moreover, the idea that our lives and the world at large were there as a resource for us to do something with was symptomatic of the Zeitgeist, as Martin Heidegger explained in his essay concerning the question of technology.

Here’s where it gets deep (so watch out). To this very day I bristle at the existential imperative, whether in secular or religious garb, that says you have to do something with your life. There are so many things that are wrong-headed about this notion that I don’t know where to start (or finish), so I’ll just highlight two logical inconsistencies that dog this everyday ethical commonplace.

First of all, “your life.” Aside from the fact that even scientists struggle to define life, what exactly about the life you live is yours? You are, after all, 90% water, which, if I understand it properly, is made of hydrogen and oxygen that has been part of this earth for some billions of years. Add to that the carbon, nitrogen, and other trace elements comprising you as physical entity, you quickly realize that none of them are “yours” strictly speaking. Indeed, your genetic peculiarities are a melange of your father’s and mother’s, as their’s were of their’s, and, in any event, consist of amino acids that are of rather ancient provenance. Etc.

So, the living matter provisionally associated with your life is freely borrowed from the environment and the vast surrounding universe to which it will inevitably return (yes, I’m referring to “your” death). But what about this “you” that is supposed to “do” something with this “life.” First of all, your “you-ness” is inextricably linked to this particular physical entity that perpetually changes (replacing itself every seven years or something like that). Not only that, your sense of yourself, your personality quirks, and your interests are totally contingent on your genetic makeup, your lived experience, and your physical condition. If you doubt this, please experiment with severe brain trauma and review the results.

But turning away from the impermanence and ineffability of your you-ness, how could you do anything with your life in the first place? Usually, in order to do something with anything, you need to distinguish between you and that something. But how can you stand outside your own life which, as we know, is not a thing in the first place? And if people mean, “Create an interesting story or artwork from the events and experiences of your life,” when they say, “Do something with your life,” why don’t they just say that?

Because, frankly, they don’t mean that. They mean, “Do things as part of your life that, retroactively, will have made your life a meaningful something instead of a meaningless nothing.” But, as everyone knows, “meaning” is entirely contextual. Nothing means anything in isolation. Which means that you can never be the judge of whether or not your own life is or was meaningful. That can only be decided by deciders who stand outside of your life and understand all its ramifications, not just in your little world, but in the history of the universe. And the number of deciders who are in a position to do that are either zero, one, or three, depending on your persuasion, none of whom are you, or even human, for that matter.

If you’ve read this far, you get the picture. From here on out, whenever anyone tells you to do something with your life, and you don’t have the time or wherewithal to explain to them what’s wrong with that statement, please have them contact me, and I’ll do the dirty work.

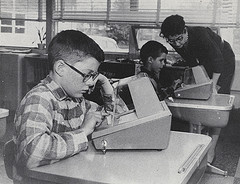

Image Courtesy of mohammadali.

Lionel Loueke is an astonishing guitar player and I would like to call the performance I saw last night at the Regattabar “virtuosic,” but that wouldn’t quite cover it.

Lionel Loueke is an astonishing guitar player and I would like to call the performance I saw last night at the Regattabar “virtuosic,” but that wouldn’t quite cover it.