Dec 2, 2012 Comments Off on Dinosaur, Jr.

Dinosaur, Jr.

A friend won some tickets so I got to go see Dinosaur, Jr. on Friday night at the Paradise.

A friend won some tickets so I got to go see Dinosaur, Jr. on Friday night at the Paradise.

They were loud, of course, but not as loud as the last time I saw them.

This time, I appreciated and understood the volume as an essential component of what they were trying to create, rather than as something that got in the way of my enjoyment.

Volume objectifies the music in a transient yet monumental way. It makes it awesome. Megalithic.

Full disclosure: It also hindered my enjoyment. My ears have too long been battered by amplified music and now certain decibel levels and certain tones are unequivocally painful.

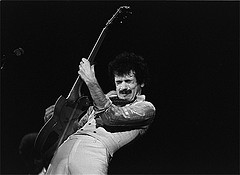

I’ve seen a lot of music over the last year and Dinosaur, Jr. reminded me of what I’d been missing from a lot of it: jamming. Dinosaur, Jr. totally jammed. And as their set progressed, J.’s solos started to stretch out. They became more involved. Elaborate. Articulate. As I wrote elsewhere, they literally blew my mind.

Before people jump on me about that “literally,” I want to stress that I mean it literally. If mind is an episodic and fluctuating state produced as our conscious brain processes external sense data, fluid, eidetic and phenomenological states, as well as the constant activity of the central nervous system, then this product (mind) was dispersed and dissipated by the music. Dust in the wind.

J. Mascis looks like a wizard (a sort of pudgy Saruman) and plays like one, his white hair swinging back and forth as he stares into the middle distance. His solos “spaced me out” as much as Garcia’s ever did. In fact, his epic coda on “Forget the Swan” at the end of the set nearly broke my head. Literally.

While undeniably punk at times, Dinosaur, Jr.’s music has its roots in 60s and 70s (Zeppelin, Rush, Neil Young, Robin Trower, etc.) and I felt, seeing them, that that was as close as I could have gotten, here in 2012, to something like Cream at the Fillmore circa 1967.

I was glad I went.

Update 12/3/2012: Just wanted to add one note on the volume issue. Yes, these guys were loud. But you could hear every single note that J. played. For most of the heavy and loud bands that I’ve heard of late, any lead playing gets lost in the sludge. Such bands would be well-served to learn from the masters.