Conservative critic Ross Douthat recently took James Cameron and Hollywood to task for rampant pantheist sympathies writing that pantheism “represents a form of religion that even atheists can support.”

Conservative critic Ross Douthat recently took James Cameron and Hollywood to task for rampant pantheist sympathies writing that pantheism “represents a form of religion that even atheists can support.”

While I believe he is mistaken to equate, as he does, pantheism with “nature worship” – the latter being more akin to polytheism or animism and the former meaning literally that God is too be found in the totality of the All, not “just” nature – I do agree that those who seek solace in natural wonders tend to be fairly selective about those parts of the natural world that they find wonderful, failing, for example, to hear the voice of God in cancer’s fatal malignancy or see the face of God in the blue sky’s indifference to atrocities unfolding ‘neath its broad, azure beams.

Though I sense Douthat’s tacit support of the Christian side of the equation, I appreciate that, in his argument against pantheism, he actually grants atheism a kind of tragic nobility:

Religion exists, in part, precisely because humans aren’t at home amid these cruel rhythms. We stand half inside the natural world and half outside it. We’re beasts with self-consciousness, predators with ethics, mortal creatures who yearn for immortality.

This is an agonized position, and if there’s no escape upward — or no God to take on flesh and come among us, as the Christmas story has it — a deeply tragic one.

Personally, what fills me with awe is the age-old human struggle to wrest sense from the senseless and to fashion purpose in the raging forge of entropic impermanence. That these efforts have about them the air of inescapable doom does indeed make them tragic.

That they can also result in moments, even epochs, of beauty, wisdom, freedom, and love, is truly divine.

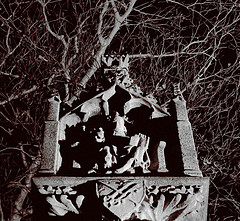

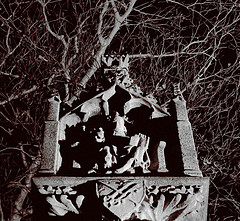

Image Courtesy of Mark Cummins.

It always puzzles me when people dismiss homosexuality, or frankly, any particular human behavior, as “unnatural.”

It always puzzles me when people dismiss homosexuality, or frankly, any particular human behavior, as “unnatural.”